In March 2025, together with her colleagues Catherine Bertram from Mission Bassin Minier in France, Mirhan Damir from the University of Alexandria in Egypt, and Helmuth Albrecht from the Technical University of Freiberg in Germany, the then Secretary General of TICCIH, Marion Steiner, visited Meiji world heritage sites and the Atom Bomb Museum and Peace Park in Nagasaki, as well as the Industrial Heritage Interpretation Center in Tokyo.

The visit was organized by the team of the Industrial Heritage Interpretation Center in Tokyo in collaboration with their partners, and masterfully coordinated by Mitsuko Nishikawa.

The programme:

Monday, 3 March 2025

* Visit of the Industrial Heritage Information Center (IHIC)

* Meeting with Koko Kato and Cabinet Secretariat

* Flight to Nagasaki

Tuesday, 4 March 2025

* Visit to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries to inspect their components parts of Meiji Japan’s property

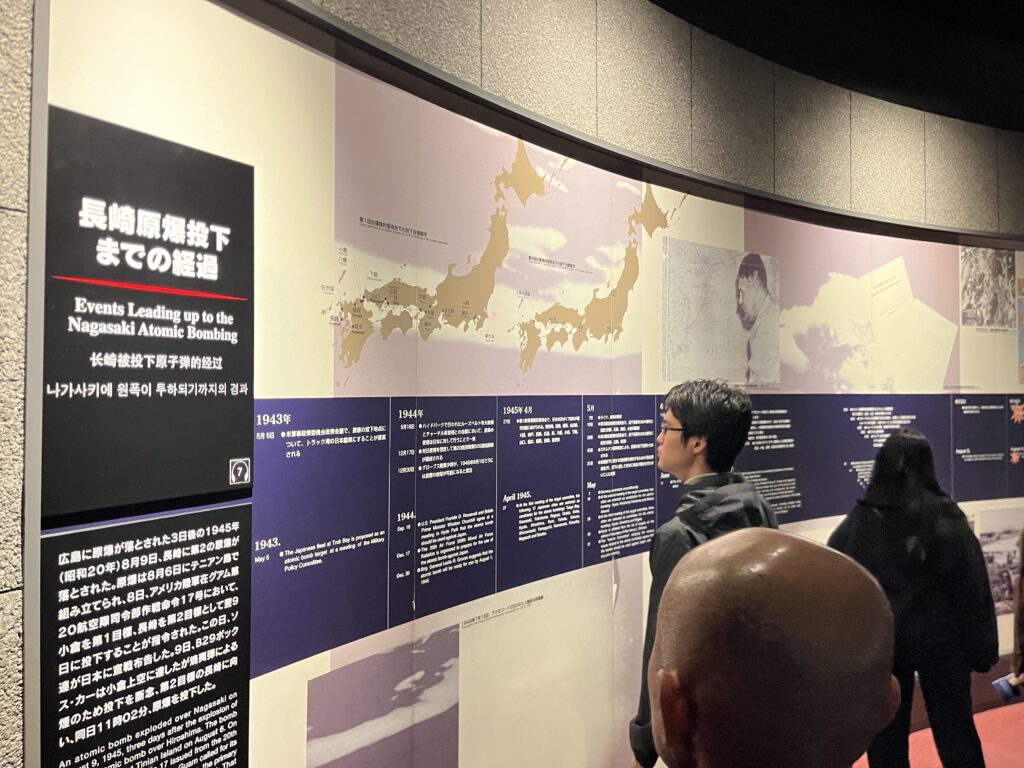

* Visit Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and Peace Park

* Technical session in the City of Nagasaki headquarters (with consecutive interpretation), including: 1. Introduction of Japan’s WH sites by Cabinet Secretariat; 2. Hashima sea wall conservation project by Nagasaki City; 3. The World Heritage Nord-Pas de Calais Mining Basin: Management system & key functions, by Catherine Bertram (inscribed in 2012; 109 components); 4. Q & A

Wednesday, 4 March 2025

* Visit to Hashima Island to inspect the latest challenge of conservation work on seawalls & embankments

* Visit to the Gunkanjima Digital Museum

* Flight back to Tokyo

Impressions from my visit to Japan for the IHIC website

Short version, Marion Steiner, 15 April 2025

In early March 2025, I was one of four international experts invited by the Industrial Heritage Information Centre (IHIC) in Tokyo, and we had an oppotunity to visit some of the component parts of the Meiji Japan’s Industrial Revolution World Heritage sites that are located in Nagasaki together with other related museums. The visit highlighted Japan’s industrial heritage and its global significance.

The visit was well-organized by IHIC, with a diverse group of experts from France, Germany, Egypt, and Chile. Our varied academic and professional backgrounds, representing non-Western countries and the Global South, allowed for valuable exchanges on industrial heritage. It was a great opportunity to reconnect with colleagues working to overcome Eurocentric approaches in the field.

As an experienced industrial heritage networker, I was especially impressed by the strong coordination between public and private sectors at the Meiji sites. Meetings with stakeholders in Tokyo, Nagasaki, and Mitsubishi revealed a unique model where a private company plays a key role in managing World Heritage sites not listed under national heritage law. The Cabinet Secretariat’s cross-ministerial collaboration and inclusion of young professionals in our visit also stood out as a forward-looking strategy to ensure the future sustainability of industrial heritage work in Japan.

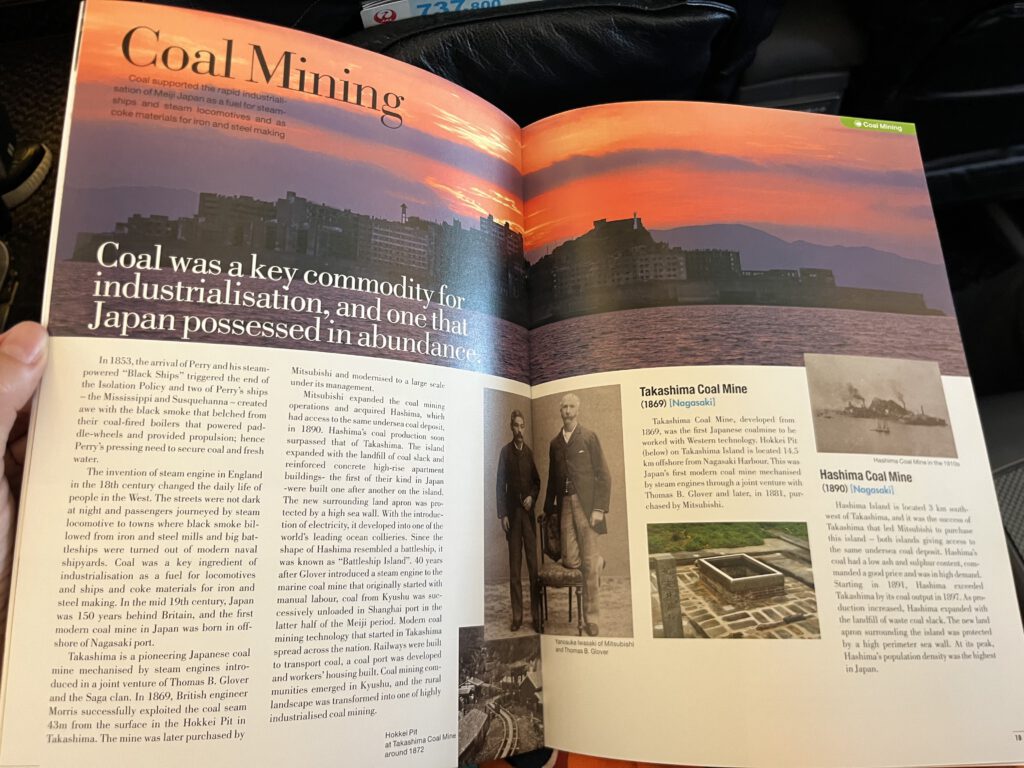

The contrast between the well-maintained Mitsubishi sites and the more complex conservation challenges of Hashima Island was striking. Hashima, decommissioned in 1974 and owned by the City of Nagasaki, was a major reason I joined the visit, especially given its relevance to Chile’s Lota Coal Mining Complex World Heritage aspirations. The ongoing conservation efforts and financial commitment across public and private sectors are remarkable, particularly from a Global South perspective. I was also intrigued by the shrine atop Hashima Island, symbolizing the link between traditional Japanese spirituality and industrialization—an aspect that deserves deeper integration into the Meiji narrative for future global dialogues.

As a global industrial heritage interpretation expert focused on the legacies of European imperialism, I valued the opportunity to explore narratives that connect communities across continents. Beyond the IHIC in Tokyo and Meiji World Heritage sites in Nagasaki, our program also included three key visits: the Gunkanjima Digital Museum, which offers a rich, immersive view of Hashima; and the Atomic Bomb Museum and Peace Park, guided by a survivor of the 1945 bombing. These sites added depth to the experience, blending education, memory, and emotional resonance in powerful ways.

There is great potential to link the story of Meiji Japan’s Industrial Revolution with broader global narratives, especially those highlighting the devastating effects of imperial power struggles. A key recommendation is to revise the cartographic representations in the exhibitions, which currently center on Europe. Re-centering maps to reflect Japan’s Pacific position could better convey its rapid industrialization as a strategic response to Western imperialism. This shift in perspective would also highlight Japan’s historic connections with other Pacific nations and underscore shared struggles for autonomy. Such changes could foster more inclusive, globally connected interpretations—and even help address current narrative conflicts by promoting a more humanistic, future-oriented message.

This vision offers powerful direction for the future of both TICCIH and UNESCO. As TICCIH moves toward revising the 2003 Nizhny Tagil Charter, there’s a vital opportunity to reframe industrial heritage not just as technical or economic history, but as a space for intercultural dialogue, confronting contested pasts, and fostering global understanding. The original mission of UNESCO—”to build peace in the minds of men and women”—is especially relevant here. Industrial heritage, when interpreted with empathy and inclusivity, can serve as a platform for compassion, solidarity, and shared human values across borders.

Photo credits:

Marion Steiner, Mirhan Damir, Catherine Bertram, Helmuth Albrecht, Mitsuko Nishikawa, Mitsubishi

**

Visit the IHIC website

Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution on UNESCO’s World Heritage list